Crossing the Thames

Why did Cliffe become one of the most important settlements in Kent?

The main reason why it attracted the attention of so many was mainly due to the ability to cross the River Thames at this point. Looking at the river today some would find it difficult to imagine a crossing at this point but it has been well documented during the past two millennia.

The original age of the crossing is uncertain but probably extends beyond the Bronze Age and this is evidenced by the number of artefacts found on either side of the Thames showing that trading between Essex and Kentish tribes was a common practice.

One of the first written records of a crossing point is by the Roman, Dion Cassius, describing the progress of Plautius, the Roman General under Emperor Claudius, in the year 43 AD.

“From there the Britons withdrew to the Thames, at a point where it flows into the sea and at high tide forms a lake. This they crossed with ease since they knew precisely where the ground was firm and the way passable. The Romans, however, in pursuing them, got into difficulties here.”

(Cassius, Dio, Roman History, Book 60, Loeb Classical Library, 9 volumes, Greek texts and facing English translation: Harvard University Press, 1914 thru 1927. Translation by Earnest Cary.)

The geology of the area shows clearly that the chalk cliff, after which Cliffe is so named, was an important feature in the landscape. It is downstream from the chalk cliff that the River Thames dramatically widens and so the location of the crossing point can easily be established. Even today it is easy to visualize the ‘lake’ reported by Cassius and, by referring to both the geology and historical and archaeological evidence, where a crossing may have been.

These crossing points (fords) were exploited by the Romans who, in turn, established a causeway and, as ships could not navigate beyond this point, a port and a road system to cater for passage of both port and crossing.

It should be pointed out that during the Roman period the River Thames was at least 9 feet lower than it is today (Devoy, 1980) or upwards of 15 feet lower according to Wheeler (R.E.M. Wheeler, London in Roman Times, London, 1930) , and what we today call the ‘marshes’ was well and truly dry land and may have continued to be so until the surges of the 13th and 15th centuries. It has been suggested that a complete Roman landscape may survive beneath 1-2m of later accretion on the Cliffe marshes. (Monaghan 1987, 28).

“The sum total of the meagre and often indirect information as to the state of the marshes from the seventh to the tenth centuries leaves a strong impression that although the land may not have been as elevated as in the Roman period it was certainly higher than now.

So much so that lands which to-day would be regularly flooded by the Spring tide were it not for the river walls, were then apparently quite free from this threat, since they were regarded as valuable meadowland.

It is difficult to imagine that the Saxons of this age had the resources to build river embankments (supposing that it was necessary to do so) around the great areas described in the Charters, and since works of this kind are never mentioned as convenient land boundaries we may assume that they did not exist. All the inferences point to the conclusion that such defences were not yet necessary.

It has been the sinking of the land with the consequent development of salt marshes which has isolated Hoo Peninsula from the North and left it in the neglected and back-water state that it is in to-day.”

(Evans J, 1953,)

The crossing points and port also gave Cliffe importance during the Saxon period too as it stood at the centre of four great kingdoms: Kent, Mercia, Anglia and Wessex. It was at Cliffe that some historians believe that the great Saxon councils were held between 700 and 800 AD.

As sea levels rose, and the land also lowered, the ford/causeway became unusable and a ferry was established to maintain the link between Kent and Essex. This ferry was, during the 12th century, recorded that maintained and fees collected by the Priory at Higham and in 1293 the prioress was found liable for maintenance of a bridge and causeway leading to the ferry.

Section from a 16th Century map of Kent showing the possibility of a ferry crossing on the Thames from Cliffe.

Much research has been carried out over the years to establish the exact location of this particular crossing point. In 1880 C. Roach-Smith, together with J. Harris, H. Wickham and M. Spurrell, set about to investigate the statement made by Hasted that:

“The place of this passage is, by many, supposed to have been from East Tilbury, in Essex, across the river to Higham (by Dr. Thorpe, Dr. Plott and otters). Between these places there was a ferry on the river; for many ages after, the usual method of intercourse between the two counties of Kent and Essex, from these parts; and it continued so till the dissolution of the Abbey here; before which time Higham was likewise the place for shipping and unshipping corn and goods, in great quantities, from this part of the country, to and from London and elsewhere. The probability of this having been a frequented ford or passage, in the time of the Romans, is strengthened by the visible remains of a raised causeway or road, near thirty feet wide, leading from the Thames side through the marshes by Higham southward to this Ridgway above-mentioned (Shorne Ridgway), and thence, across the London highroad on Gad's Hill, to Shorne Ridgway, about half-a-mile beyond, which adjoins the Roman Watling-street road near the entrance into Cobham Park. In the Pleas of the Crown in the 21st year of King Edward I, the Prioress of the nunnery of Higham was found liable to maintain a bridge and causeway that led from Higham down to the river Thames, in order to give the better and easier passage to such as would ferry from thence into Essex."

In their research they found a raised causeway of about thirty feet wide and travelling in a straight line towards the Thames, at a point opposite East Tilbury in Essex. They concurred that its height would enable it to be in use all year and, although then out of use, still bore numerous cart and wagon ruts showing its use as a highroad. It continues:

“The notion that the land up to, and beyond. Lower Higham, was subject to submergence in historic times, is refuted by the discovery of Roman burials, in the low ground, opposite the old ferry house. The newly-made graves, in Higham churchyard, continually disclose fragments of Roman pottery and tiles, contributing to shew that the district was well populated in the Roman epoch.

I have, from evidences such as these, ever felt that there has been by no means such changes, in the low sea-marginal lands, during the historic period, as has been imagined by many.”

The full text of this report can be seen at the end of this article.

The last reference to a crossing point still in use is during the middle of the sixteenth century although in 1293 it has been recorded that the causeway at Higham from which the Higham Ferry crossed the river to Essex was totally destroyed in a storm.

The Roman road towards Tilbury attests to the importance of this area in accessing the Thames and the historic crossing point to Cliffe. On the Essex side the road appears to belong to a north-south route which passes through Billericay and Chelmsford, dividing at Little Waltham. Two bronze skillets, if they are of this period, said to have been found near Cliffe and now in the Rochester Museum, may have come from a fort overlooking this crucial crossing point.

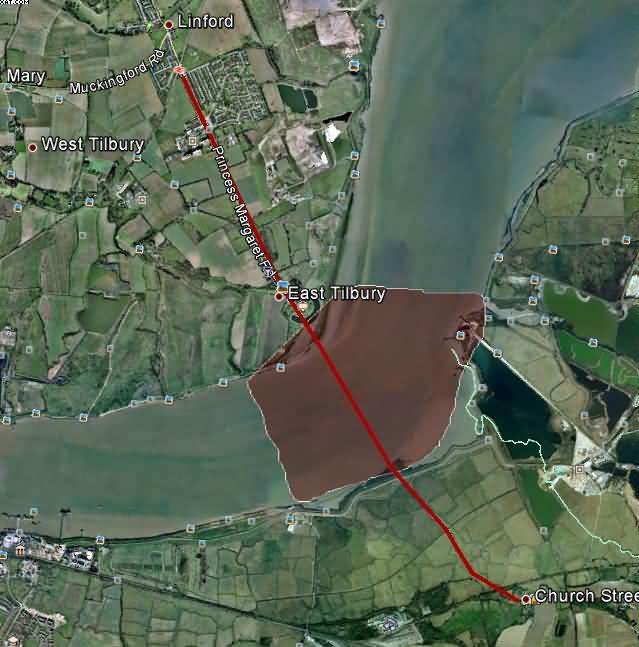

The red line shows the link between Kent and Essex. The lighter red shows the most likely areas in which a ford may have been.

As sea levels rose the fords became unusable and ferry/ferries took their place. There was at least one port situated at Cliffe – possibly two with one situated at Cliffe Creek and the other at Cliffe Fleet: both linked by excellent road systems. In March 1301 it is recorded that King Edward I ordered a general levy of ships to be sent into Scottish waters as part of his campaign to subdue this constant thorn in English diplomacy. Amongst the ports mentioned, was that of Cliffe which had to supply one vessel. In the year 1326, Cliffe was mentioned as a port and, again with references to a significant port at Cliffe Creek - it is said to have provided Edward III with two ships in 1346 for his campaign in France (Cracknell 2005). In 1380, when it was recorded as having one 80—ton vessel stationed there. Finally, in 1417, two ships were hired from Cliffe as part of Henry V’s campaign in France.

With the land around Cliffe subjected to the constant danger of flooding, the numerous creeks silting up, the raising of the sea level enabling the Thames to be navigable further upstream, the consequence of the Henry VIII’s moves to reduce the influence of the church and other factors the crossings and ports became obsolete.

THE SHORNE, HIGHAM, AND CLIFFE MARSHES.

BY C. ROACH SMITH.

I was on the point of visiting the marshes between Higham and the Thames, in order to ascertain the correctness of Hasted, who describes a Roman causeway there, when the reception of a publication, by Mr. Thomas Kerslake of Bristol, (in which this causeway is referred to, as evidence of the early state of these marshes,) gave me an additional motive to proceed in my object, without futher delay. I have now paid five visits to the marshes; chiefly in company with Mr. Humphry Wickham, and Mr. John Harris. Once we were joined by Mr. Maxman Spurrell, who, it appears, has been for some time examining the marshes in relation to their ancient embankments, and the condition of the Thames anterior to, and during, the Roman domination. Hasted's statement is as follows:—

"Plautius, the Roman General under the Emperor Claudius, in the year of Christ 43, is said to have passed the River Thames from Essex into Kent, near the mouth of it, with his army, in pursuit of the flying Britons, who, being acquainted with the firm and fordable places of it, passed it easily (Dion Cassius, lib. lx.) The place of this passage is, by many, supposed to have been from East Tilbury, in Essex, across the river to Higham (by Dr. Thorpe, Dr. Plott and others). Between these places there was a ferry on the river; for many ages after, the usual method of intercourse between the two counties of Kent and Essex, from these parts; and it continued so till the dissolution of the Abbey here; before which time Higham was likewise the place for shipping and unshipping corn and goods, in great quantities, from this part of the country, to and from London and elsewhere. The probability of this having been a frequented ford or passage, in the time of the Romans, is strengthened by the visible remains of a raised causeway or road, near thirty feet wide, leading from the Thames side through the marshes by Higham southward to this Ridgway above-mentioned (Shorne Ridgway), and thence, across the London highroad on Gad's Hill, to Shorne Ridgway, about half-a-mile beyond, which adjoins the Roman Watling-street road near the entrance into Cobham Park. In the Pleas of the Crown in the 21st year of King Edward I, the Prioress of the nunnery of Higham was found liable to maintain a bridge and causeway that led from Higham down to the river Thames, in order to give the better and easier passage to such as would ferry from thence into Essex."

Dion Cassius, mentioned by Hasted, is more diffuse on the exploits of Aulus Plautius than would be expected from this reference. The notes of Ward, printed by Horsley in his Britannia Romano, pp. 23 to 25, should be compared with the account given by Dion Cassius. This is highly important, as shewing the extent of marshy, unembanked land on the banks of the Thames, which, known to the Britons, caused the Romans great difficulties and loss of men. It may be safely inferred that both the embankment and the causeway, the object of our visits, were constructed soon after the perfect subjugation of Britain, which followed the invasion under Aiilus Plautius and the Emperor Claudius in person.

Following a straight line from the highroad, which leads from Shorne Ridgway to the church at Lower Higham, we crossed a farm yard and a meadow; we then came upon an embankment, which we, at first, supposed to be the causeway mentioned by Hasted; but subsequent visits shewed that the two works were perfectly distinct. This embankment is a work of great engineering skill, and must have cost much time and labour. It belongs to, and is portion of, the extensive embankment of the Thames; but, to within a short distance from the river, it forms a grand combination of embankment and causeway, running generally in a straight line where it is possible to do so. Often, however, it deviates; evidently with a view to make available, on the western side, an ancient creek, which throughout has regulated its course. This creek causes turnings which were unavoidable to the constructors, who had decided on making use of it. They probably widened and deepened the creek. On the eastern side runs another creek, also accompanying the embankment throughout its course. This appears to have been cut to help form the raised ground ; while it also forms a land boundary, as does its wider companion on the western side. The base, of this great work, may be computed at about twenty-five feet, at the level of the marsh land; and it rises to the height of twelve to fifteen feet. On the side of the Thames, towards Gravesend, it is fully twenty feet high. Here it diminishes in width, at the top, to about three feet, from about six feet.

This important work branches off, at about half a mile from the Thames, to Cliffe; and, nearly a quarter of a mile onwards, to Gravesend. The Cliffe branch is very winding; and it shews, throughout, how its construction was regulated by local circumstances. It was built to secure from inundation all the better land, leaving to its fate, as not worth reclaiming, the portion nearer the Thames. The same was the case with the land on the western side. From the spot where is the divarication from the straight line from Higham, for a very considerable distance, a wide space of ground on the margin of the Thames is unenclosed. It was thought worthless; and over it the high tides have ever flowed and still flow. But the vast tract, of marsh and meadow land, protected by the embankment, has apparently been ever secured from the highest tides. Sheep and cattle graze upon it, in perfect security; it grows no marine plants, such as flourish on the river side; its creeks are full of fresh water plants, and fresh water fish.

Following the embankment to Gravesend, we noticed a very marked causeway, in the marsh, which seemed to point from Higham to a spot not very far from Gravesend.' It was in our endeavour, on a subsequent day, to trace this raised road, nearly thirty feet wide at its base, that we came upon Hasted's causeway. That, which was the immediate object of our search, was so intersected by water courses, cut since its discontinuance as a road, that, in endeavouring to recover it, by a long circuit towards the high ground at Beckly, we approached Higham in a new direction, and came upon the causeway at the upper part, near the village of Higham. It answers Hasted's description; is fully thirty feet wide; and in a pretty straight line, goes direct to the Thames, at a point opposite East Tilbury in Essex. Its elevation is sufficiently high to make it, at all seasons, fit for traffic of all kinds; and, though it be now somewhat out of repair, it bears, in numerous cart and waggon ruts, the marks of use as a highroad at a very recent period. If, instead of passing Higham church, towards the marshes, the road on the left be taken, and followed, in front of the houses and past them, the causeway will be found at a short distance. The last of these houses, the "Sun" Beershop, bears also the significant name of the "Old Ferry House."

The magnitude, extent, and efficiency of these works, which I have attempted thus briefly to describe, point, I submit, to Roman origin. The absence of all evidence of the period of their construction, in historical or documentary works, tends to testimony in favour of remote antiquity. The notion that the land up to, and beyond. Lower Higham, was subject to submergence in historic times, is refuted by the discovery of Roman burials, in the low ground, opposite the old ferry house. I refer to Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. XI., p. 113. The newly-made graves, in Higham churchyard, continually disclose fragments of Roman pottery and tiles, contributing to shew that the district was well populated in the Roman epoch.

I have, from evidences such as these, ever felt that there has been by no means such changes, in the low sea-marginal lands, during the historic period, as has been imagined by many.

Mr. Kerslake, in the paper I have referred to in the commencement of any remarks, has brought together many important evidences of the intercourse of Essex with Kent, by the Trajectus between East Tilbury and Higham, from the seventh to the tenth century; and these could, no doubt, be easily added to. He has also collected a large mass of valuable materials respecting the state of the entire district from Higham to Hoo, including the long disputed position of Cloveshoe, where, from the eighth century, so many royal and pontifical Councils were held.

This he, with some of our best modern authorities, shews to be Cliffe-at-Hoo. He adduces, also, auxiliary evidence in the records of these convocations, to prove that the places designated "Cealchythe" and "Acle," are now represented by "Chalk," and "Oakley," near Higham.

The importance of these meetings, which were witenagemdts, or parliaments, as well as ecclesiastical synods, is shewn in the late JM. Kemble's Saxons in England, vol. ii, p. 241, et seq. He cites numerous instances, extending, as regards these localities, from the seventh to the tenth century; but this accomplished scholar did not perceive, like Mr. Kerslake, their claims to a Kentish site.

Under the guidance of the Rev. H. H. Lloyd, we examined the church of Cliffe and its environs, but failed to find any ruins of buildings assignable to the times of the great Councils. The foundation of the long wall, on the north of the church, appears to be of the same date as that edifice, and both contain broken gravestones used as building materials; but they are not, perhaps, above a century or two anterior.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Kent Archaeological Society.