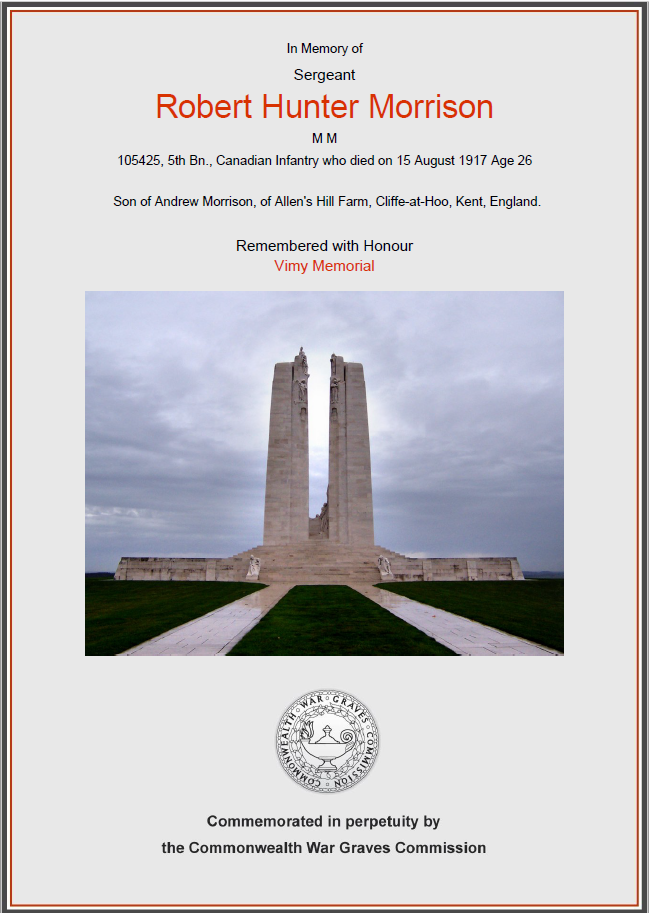

Robert Hunter Morrison

18 June 1891 – 15 August 1917

“At dawn on August 15, ten Canadian battalions rose from their trenches and walked into the barrage. In front of them Hill 70 erupted in explosions of flame and dirt……Thick smoke from 500 blazing oil barrels spread as a screen over Hill 70, blinding German machine gunners…..in twenty minutes the surviving Canadians were on top of Hill 70.”

By Desmond Moreton.

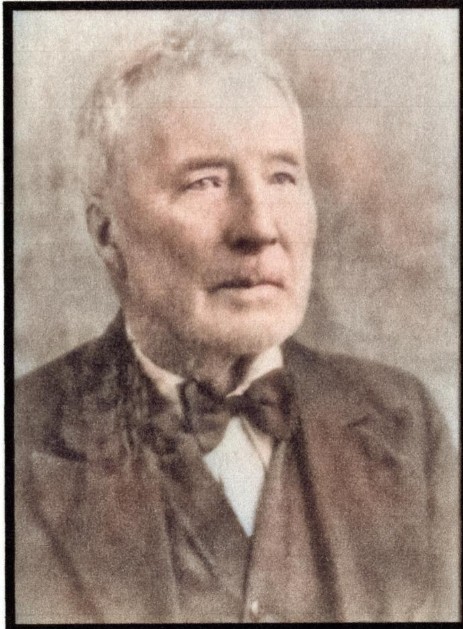

Robert Morrison was one of 19 children born to Andrew and Elizabeth Morrison neé Rankin who married in Scotland on 28th November 1884.

The family moved to Cliffe from Scotland where several of their children had been born. Mr Morrison was a partially qualified Veterinary Surgeon whose skill in taking care of sick animals soon made him popular with the local farmers.

The family moved from Walnut Tree Cottage to Allen’s Hill sometime before 1911 and Andrew describes himself, on the 1911 Census, as a dairy farmer working for Robert Robertson, a farmer and grazier of Manor Farm.

The village of Cliffe, although enjoying prosperity through the introduction of the Whiting, Cement and Cordite factories, was by and large still rural.

The introduction of employment opportunities that were not dependant on farming, had impacted on working practices meaning that old farm labourers now had to shop for food. The introduction of a bus service in July 1914 enabled the population to become more mobile but it was unlikely that the vast majority would have able to afford the 7d. it cost to travel to Chatham unless it was for a special occasion. So village residents were mostly reliant on the village shops that provided the day to day necessities of life.

Mr Morrison would have been a busy man tending to the health of the farm animals of the local farmers and to the dairy herd of Mr Robertson. In total 6 slaughter houses kept the village butchers supplied with meat to feed the 2,465 people counted on the 1911 Census records and it is noted that one of Mr Morrison’s son was a butcher.

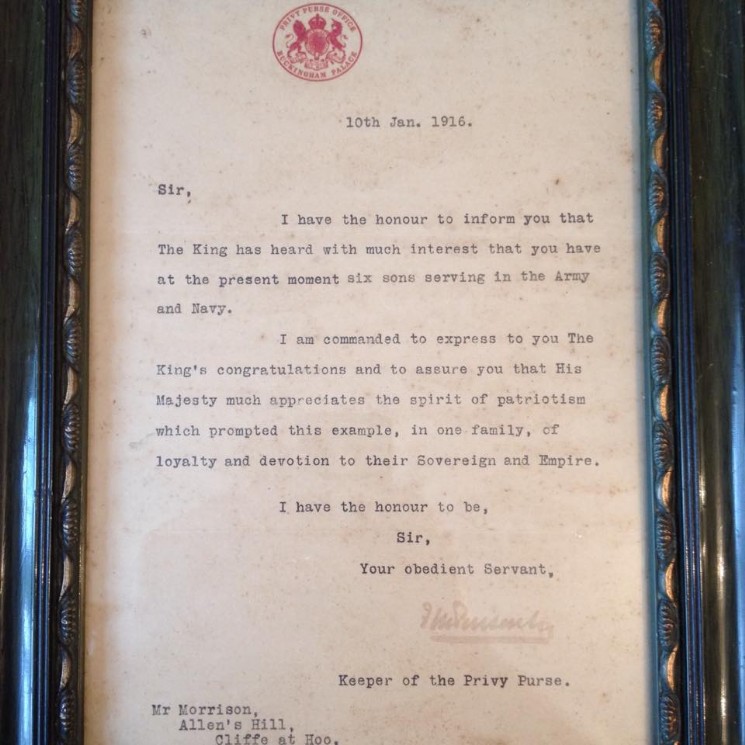

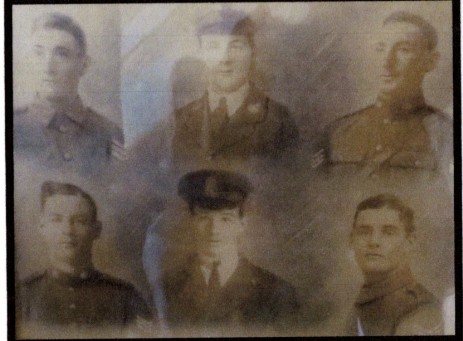

Three of Andrew’s sons emigrated to Canada between 1905 & 1912 but then war broke out, and soon the Canadian men were called to arms. Andrew and his wife actually had six of their sons serving in the armed forces.

Sergeant George Edward Morrison was born on the 31st October 1893 and had begun a new life as a farmer in Balcarres, Saskatoon arriving on the SS Pretorian from Glasgow in 1909 aged 15. George enlisted, aged 21, in Regina, Saskatchewan on 29th November 1915, and served with the Canadian Infantry (Princes Patricia’s Own Machine Gun Section). He won a Military Medal for bravery in the field.

John Rankin Morrison (known as Jack) was born on the 3rd October 1888 and left for Canada in 1905 aged 17 on board the SS Corinthian and enlisted, aged 26, in Regina, Saskatchewan on the 2nd June 1915 stating his religion as Wesleyan.

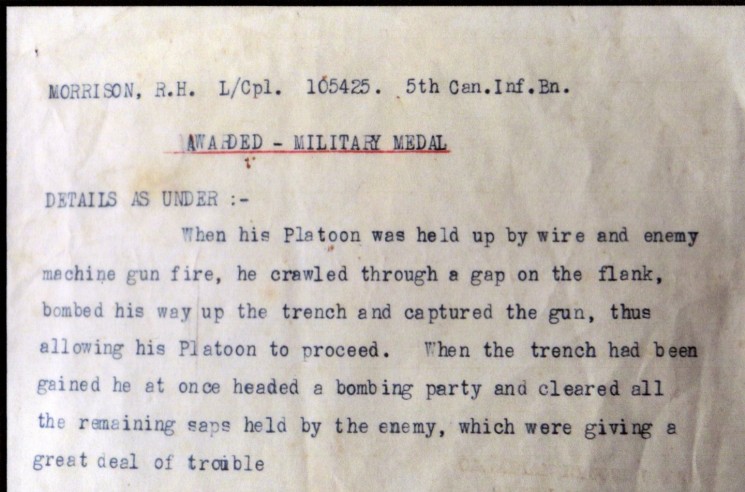

Robert Hunter Morrison was born on 18th June 1891 and emigrated to a farm in Balcarres, Saskatoon, Canada on the SS Teutonic on 9th March 1912. He enlisted aged 23, in Regina and joined the 5th Battalion Canadian Light Infantry on the 24th November 1915. Robert, known as Bob, won the Military Medal about 6 weeks before his death on 15th August 1917.

A letter from from the King expressing his admiration for the six sons from the Morrison family serving in the forces.

The newspaper correspondent for Cliffe village, Mr Briggs, wrote in The Chatham News, 1st September 1917:

“Official news was received on Tuesday of the death of Bob Morrison who was killed in action on the 15th/16th August. He was a Sergeant in the 5th Canadian Light Infantry Regiment and had been awarded for bravery the Military Medal just 6 weeks previously. He was a promising young fellow of 25 and had been recommended for a commission. He was due home in a few days for the purpose of taking up his commission.”

Robert died in the Battle for Hill 70 as pictured above from the Canadian Great War Project and was in the same company as Lieutenant Walsh who was on the extreme right of the advance.

This is an extract about the events leading up to the day Robert Morrison died taken from the Canadian Official History of the First World War from the Canadian Army War Diaries.

“Currie was a superb tactician, one of the best military minds of all time. He was incredibly sensitive about the use of troops, and his actions as commander likely save may thousands of lives. He was also incredibly insensitive in his dealings with the rank and file and was dislike by the troops.

On July 7th, 1917 Currie was ordered to take the town of Lens in northern France. The town was strategic; the Germans needed it for its rail access, the British wanted it for its coal, which they needed to support war manufacturing. Additionally, the British wanted to use the attack as a feint, committing German troops to Lens while the British and French attacked in the Somme area.

Currie refused a frontal attack on Lens. He felt that the troops could take the town, but would find itself under attack from the high ground that surrounded the town. He believed that the losses would be unacceptably high, and instead proposed to take Hill 70, high ground to the north of Lens. He knew that it would not be easy to take and that casualties would be high, but they would be considerably less than leaving the hill in the hands of the Germans. Currie argued that the Germans would attempt to retake the hill and the Canadians would have the advantage of having the higher ground and would be able to inflict significant losses on the Germans. The British Army structure did not appreciate Generals changing orders instead of following them, and the issue was raised to Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, Commander in Chief of the British forces. Haig approved of the attack but predicted it would fail.

Hill 70 was a perfect defensive position. It was a maze of deep trenches and dugouts and included deep mines that had been dug in peacetime and could protect the defenders. Coiled barbed wired, up to 5 feet in height, was in front of the trenches and would make a frontal assault difficult. Machine guns were deeply entrenched in the slopes inside pillboxes of reinforced concrete. Additionally, in July 1917, the Germans introduced flame throwers and mustard gas, which blistered any potion of exposed skin. Overall it wasn’t an enviable target to be given.

Preparations for the attack were extensive. As they had done at Vimy, an area behind the lines was laid out to represent Hill 70, and units practiced the attack until every section knew exactly what they had to do. Additionally the hill and the surrounding area was subjected to ongoing bombardment and gas attacks. The gas, being heavier than air, would have sunk to the lowest areas of the trenches and caverns, and would have made it very uncomfortable for the German defenders.

On the evening of the 14th August the attack commenced with the bombardment of the hill by the Canadian artillery, damaging the trenches and blowing holes in the defensive wire. At 4:26 am, dawn of August 1915, the Canadians went ‘over the top’, the 1st Division on the left, 2nd in the centre and the 4th Division, a largely diversionary attack, on the right: the 3rd Division were held back in reserve. The ten battalions of men advanced up the hill, closely following a rolling barrage by artillery. They took the first objective in twenty minutes. The Canadians introduced a new tactic to demoralise the Germans. Drums of burning oil were dropped into the deep trenches, spreading flames and smoke over the hill. Another feature of the attack on Hill 70 was the close co-operation between the Air Force and the Artillery. Low flying aircraft spotted pockets of resistance and radioed the co-ordinates back to the artillery who responded with prompt shelling.

By 9:00am the Germans has begun to counter-attack, fought off by the Canadians troops on the hill and the artillery in support. The artillery crews suffered heavily. The Germans recognised that without them the attack would fail, and started a barrage of high explosive and Mustard Gas shells. The day was hot and being forced, because of the gas, to work fully clothed and with gas masks, several men from heat prostration. Wearing a gas mask rendered the men half blind, but removing them could cause a horrible death as the Mustard Gas seared the lungs. Many men had to remove their masks, whether to accurately aim the guns or to extricate themselves from holes or wire on the hill slopes, and suffered from facial and internal blistering as a result.

The Germans were determined to retake the hill. The Canadians were subjected to intense artillery shelling, suffered from lack of rations and water, and when ammunition ran low had to attack with bayonets. On August 21st, the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles took over the front lines. They described the situation: “At this time the Hill presented every aspect of a fierce and sanguinary battle; most of the Germans trenches had been crumpled in by out shell fire, while everywhere one went were dead Huns and, in some cases, Canadians.”

In total, the German counterattacked 21 times, the last at dawn on August 18th. The Canadians repulsed them all.

The attack on Hill 70 resulted in 1,505 men killed, 3,810 wounded, 487 wounded by gas and 41 prisoners to the Germans.

The bulk of the casualties were on the first day of the attack. In some cases companies reached and held their objectives while sustaining over 70% casualties. The Germans had committed 5 divisions in an attempt to hold Hill 70, with approximately 20,000 causalities, 970 Germans taken prisoner.

Lens was not taken, however holding the high ground of Hill 70 seriously impacted the German position.

Military ‘Death Penny’ of Robert Hunter Morrison

The Morrison family to which he belonged had a further 3 sons serving, the oldest son Andrew had been awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal whilst serving in Egypt in 1916 with the Armoured Car Battery and James, who had been wounded 4 times, was in hospital in France at the time of his brother Robert’s death.

This is a photograph of the family portrait of the six Morrison boys

This is the Memorial to those who died in the battle for Hill 70 which was unveiled on the 22nd August 2017. This monument came about through the efforts of the Canadian Hill 70 Project as a tribute to the terrible struggle of over 100,000 men who fought over a slight ridge of land which cost 1,500 of their lives.

Thank you to Janet and Graeme Walkinshaw for their help in facilitating and helping organise the information this feature about Robert Morrison.

Researched & written by Janet Keats.