Cooling Castle

Today, just laying to the east of Cliffe, is the parish of Cooling whose boundary has fluctuated over time and was once very much part of the landscape of Cliffe and the fields and marshes. At Cooling, since the late 14th century, stands the impressive site of Cooling Castle: a Grade I listed building.

Cooling Castle is quite unusual in form as it was not constructed on a single moated island as was the case for most quadrangular castles. It preserves one of the finest gatehouses of any castle in Kent, its twin towers top-heavy with their machicolated parapets. There are considerable remains of the rest of the castle too, which was built in the 1380s in response to the French threat of invasion. Roman and Saxon settlements have been located near the castle site, and a manor house has stood there at least since Norman times.

The manor of Cooling was acquired by the de Cobham family by the middle of the 13th century and John de Cobham, the 3rd Baron Cobham, used the French raid on the Thames estuary in 1379, part of the hostilities of the 100 Years War between England and France, to justify the need for a castle to protect northern Kent, the port at Cliffe and the seaward approach to London.

He received Royal licence from Richard II to fortify his manor on 2nd February 1380-1, and building work was completed by the end of 1385.

The inner ward was built first and was occupied throughout the building operations. The castle seems to have been largely complete by as early as 1385, and the building accounts survive almost in their entirety. Within thirteen years however, Sir John de Cobham was banished to Guernsey because of his part in a baronial dispute with the King. When Richard II died a few years later, his successor, Henry IV, allowed Sir John to reclaim his estates. Sir John died in 1408.

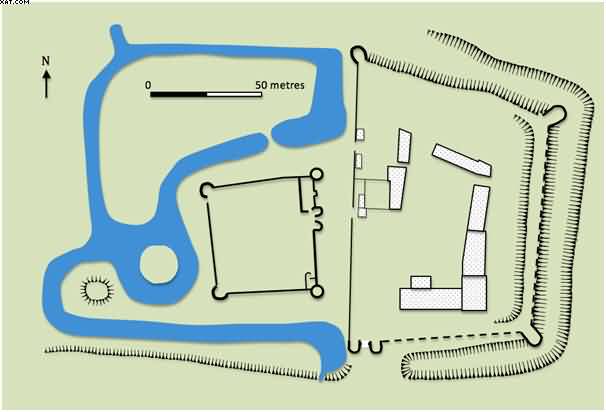

Plan of Cooling Castle (not based on an original survey but is compiled from a variety of published sources) courtesy of Stephen Wass

Sir John’s only child, a daughter, had died before him, so Cooling passed to his grand-daughter, Joan. She married four times, on the fourth occasion to Sir John Oldcastle, but he was killed before she herself died. Although the title Lord Cobham remained, the estates passed to other families through the female line.

The most famous event to take place at the castle was the siege of 1554. It lasted for one day - the 30th January. The then Lord Cobham was George Brooke, whose sister was married to Sir Thomas Wyatt, of nearby Allington Castle. Wyatt led a rebellion in Kent to protest at the proposed marriage between Queen Mary and Philip of Spain.

On 28th January, Lord Cobham went to Gravesend to meet with other Royalist nobles and the Duke of Norfolk. The Duke had brought an army of six hundred Whitecoats and six guns from London to crush Wyatt’s rebellion, but was defeated at Strood the following day. Many of the Whitecoats deserted the Duke and joined Wyatt, who then marched with his newly captured guns, against his brother-in-law, Lord Cobham, at Cooling Castle.

Cobham had only a handful of men (some reports say as few as eight) and virtually no arms with which to defend his castle. When Wyatt arrived at Cooling on the 30th January he trained two of his cannons on the main gate and four against the curtain wall. Within a very short space of time he succeeded in taking the outer ward and then set his guns against the inner gatehouse. A few hours later Cobham surrendered. The siege, which had begun at 11am, was all over by 5pm the same day.

Some of Cobham’s men were dead, most were wounded, and the castle was badly damaged. He wrote a letter to Queen Mary explaining what had happened and that he had been unable to stop Wyatt. Later, when the rebellion had been squashed, Mary had Lord Cobham and his sons imprisoned in the Tower of London. Thomas Cobham, the youngest son, carved his name on the wall of their prison in the Beauchamp Tower, which can still be seen today. The Cobham family were restored to their estates, however, by the 24th March of the same year.

In the supplementary notes to ‘The Historical Archaeology of England’ we read that, ‘Matthew Johnson uses Cooling as the first example in his 2002 book 'Behind the Castle Gate: Medieval to Renaissance' to critique the simplistic military interpretation of medieval castle architecture’(HAE 2011). Indeed he does and in some respects Cooling seems an easy target with its exaggerated profiles and flimsy walls (Fig. 11). Most telling is its apparent vulnerability to a brief attack with the defenders capitulating after a few hours thus destroying any military credibility. A closer examination of the events of 1554 may give us pause for thought:

'Wyatt’s force, 2,000 strong, came before the castle at eleven o’clock A.M. and battered the great entrance of the outer ward with two great guns, while the other four were laid against another side of the castle. Lord Cobham defended his house with his three sons and a handful of men till five o’clock in the evening, having no weapons but four or five handguns; several of his men had then been killed, the ammunition was nearly expended, and the gates and drawbridge so injured that his men began to murmur and mutiny. So he was obliged to yield' (Mackenzie 1896: 11).

However unconvincing we may feel Cooling Castle is as a military structure it enabled Cobham to mount a sufficiently effective defence by a small household against a much larger attacking force. When he was later arrested by Elizabeth the simple fact of his stout resistance may have been enough to save his life.

After the siege, Cooling Castle was never fully repaired and the Cobham family never again lived there. Their other property, Cobham Hall, became their chief residence, and Cooling Castle was allowed to gently fall into disrepair. The castle estates soon reverted to their original use of farmland, and in the 19th century tenant farmers erected a number of agricultural buildings in the outer ward. A former owner of the castle found fallen masonry and iron and stone cannon balls in the eastern arm of the moat during the 19th century.

The castle was acquired by the Knight’s, a local shipping family, who were responsible for much of the restoration work at the castle. There are considerable remains, especially in the inner ward, and in fairly good condition. The castle is now owned by the musician, Jools Holland who too works towards the upkeep and restoration of the castle.

The castle consists of two rectangular wards, separated from one another and surrounded by a figure of eight moat. The larger, outer enclosure contained the principle gatehouse and was connected to the mainland by a drawbridge. The inner ward however, stood on an island in the moat and was only accessible from the outer ward. The castle buildings themselves occupy approximately three-and-a-half acres, but including the water defences, this area extends to double that.

Henry Yevelle is known to have been at the site during building operations and is reputed to be the designer. In order to speed up the building, John de Cobham employed the services of a number of different masons, allotting each one a specific section of the castle to build. Both William Sharnall and Thomas Crump, a Maidstone man, have at various times been credited with the design and construction of the outer gatehouse. It is coursed ragstone with some knapped flint. 2 semi-circular towers with boldly projecting rings of machicolations and crenellations. Four-centred arch between with crenellations above and moulded round-arched gateway below and behind. Single loopholes on front faces of towers at half height. The gatehouse is open on the inside and originally admitted to the extreme south-west corner of the outer ward. The building accounts show that it was completed by 23rd July 1382 and cost £456.

The gunloops in the outer gatehouse, similar ones of which are to be found elsewhere at the castle, would appear to have been provided from the start. They are of two types - keyhole shape loops for small handguns, and larger plain circular porthole type openings. In the latter examples, guns were mounted in the internal embrasures behind the openings, and trained onto certain fixed spots on the ground outside the castle. They could not be elevated and consequently could only be fired when an attacking force were within its limited range.

The inner ward at Cooling was much higher than the outer one so as to overlook and command it. Being in a rural position there was rarely sufficient manpower available to effectively defend the castle. The idea was that a small number of men could man the inner ward and to some extent protect the outer ward. Because the inner ward could not be reached from the mainland, the outer ward had first to be taken by an attacker seeking entry. The main gatehouse and corner towers were back-less so that if it were captured it would afford no protective cover to an assailant, who would also be exposed to fire from the walls of the inner ward.

All of the residential apartments were confined to the inner ward, the buildings being arranged around its four sides in the typical fashion of a courtyard castle. The outer ward was reserved for outbuildings, livestock, and the local inhabitants in times of trouble. The gatehouse in the south-west corner was the only substantial building in the outer ward. It stands virtually complete to a height of about 40ft (12.2m). It was 50ft (15.2m) wide overall and about 25ft (7.6m) deep including its D-shaped towers. The actual gateway was 9ft (2.7m) wide by 15ft (4.6m) high and was protected by a drawbridge, a pair of folding doors and machicolations, but there was no portcullis.

The gate passage originally had a vaulted roof. There are twelve machicolations encicling the west tower and eleven on the eastern tower, with a long slot divided into three similar openings above the gateway itself. Attached to the side of the eastern tower is an inscription by Sir John de Cobham, giving his reasons for erecting the castle. It is written in English, which was rare for the time, and in rhyme, and reads:

“Knouwyth that beth and schul be

That I am mad in help of the cuntre

In knowyng of whyche thyng

Thys is chartre and wytnessyng.”

It is possible, however, that the inscription was put up after the siege of 1554 by Lord Cobham, to please Queen Mary. Considerable portions of the curtain wall and corner towers remain from the outer ward. Remains of the inner ward are even more substantial. Of the four corner towers, one survives almost in its entirety, one is half ruined, one is reduced to its lower levels only, and one has been demolished, although its internal features can be seen on the curtain wall. On the western side is a postern, near to the north-west tower and protected by a row of machicolations. A row of exotic palm trees also line this wall. Not only are the walls of the inner court higher than those of the outer, the ground level is also higher, perhaps embodying an earlier mound.

The inner gatehouse is much smaller than the outer one, but is almost as well preserved. A bridge is connected to the outer ward, with a drawbridge at its inner end. The inner gatehouse was also provisioned with keyhole shaped gunloops and a portcullis. The drawbridge was of the type where two timbers passed out horizontally through slots which, when drawn in, pulled up the drawbridge.

The north-east corner of the inner ward is a delightful room which was either the undercroft for the hall above, or a chapel. It is a highly decorative room and may have been either. It outer walls are decorated with a chequer pattern, an effect created by the alternating use of flint and stone in rectangular blocks. The room originally connected to one of the corner towers, but this has now gone. There are niches in the outer wall, possibly for holy vessels if the room was a chapel, which would originally have been inside the tower. The walls of the inner court are built from Kentish ragstone with ashlar dressings, but with a chalk core. Part of the vaulting in the chequered room survives revealing the squared, chalk blocks.

The south-east tower, the most complete one, has a basement with loops in the wall to protect the moat and area between the two wards. Unfortunately, none of the other buildings of the inner ward have survived, but corbels jutting out from the wall faces show where they were positioned. Part of the outer moat still survives, and is now frequented by herons from a nearby nature reserve. The remainder of the moat has been partly filled in and laid to lawn. The castle stands on private land and is not open to the public, but much of the castle can be clearly seen from the road, particularly the outer gatehouse and inner ward.

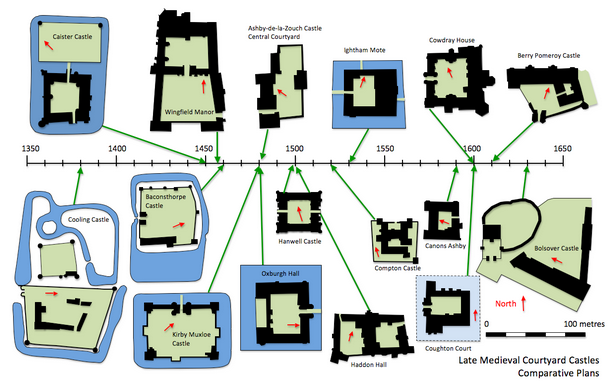

Below is a timeline showing the development of Medieval Courtyard Castles, courtesy of Mr Stephen Waas. For more information please see Stephen's site on: http://www.polyolbion.org.uk/