The Old Rectory

Just to the south of the existing main focus of the village of Cliffe and west of the former Cliffe railway station stands an impressive building: that of the Old Rectory. The exact date of the first building is unknown but early records begin in the early 14th century, although it is strongly suggested that the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, built himself a manor house here in the early 13th century.

What is certain is that the Prior of Christ Church Canterbury gave a licence in 1333 to the Rector of Clyve permitting the celebration of divine service in the chapel dedicated to St Lawrence within the house.

In 1337 the hall was to be rebuilt, at great expense, by Bishop of Rochester (Hame de Hethe) and that Lawrence Fastolf built an Oratory Chapel built in 1348, which was consecrated the following year. According to the Historic Environment Records of Kent County Council details the later damage caused during the periods of civil disturbance by Watt Tyler’s men from the Peasants Revolt in 1378 and/or Jack Cade’s forces in the 1450’s rebellion.

The Rectory housed the rectors of Cliffe which included: two chancellors of the exchequer, two archbishops, three deans and 11 archdeacons. Nicholas Heath, Bishop of Rochester and Bishop of Worcester also lived at the rectory. The 'living' at Cliffe in the 17th century was described as 'one of the prizes of the church'.

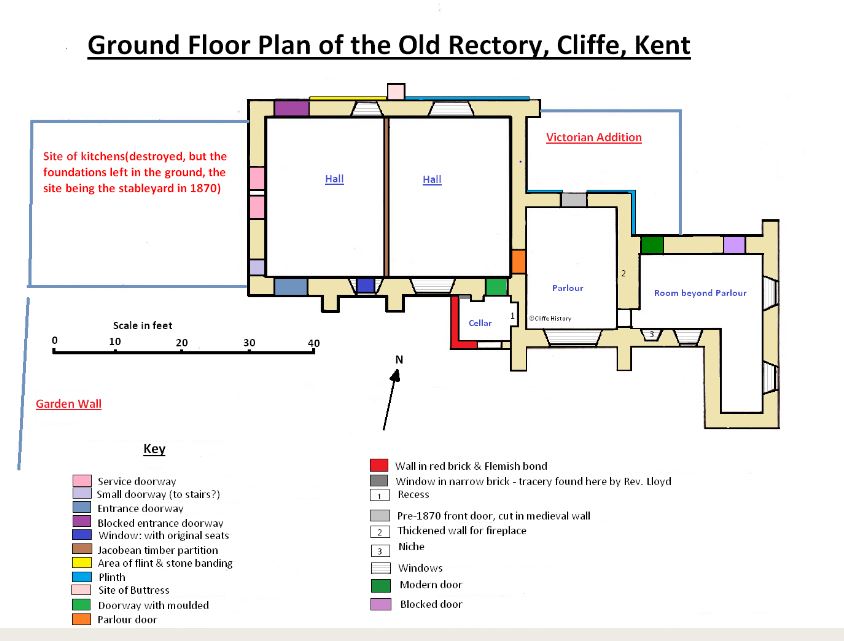

The Rectory House was of a size commensurate with its importance, having a hall of internal length 37 ft. 9 in. and internal width 24 ft. 9 in. The Rev. Henry Robert Lloyd was sixty when he was instituted in 1869 and was the first resident rector for many years. He also commenced a campaign of restoration at the church (Gray, 1978), much at his own expense. At the Rectory House, he recognised the significance of the building and explained how he had discovered and opened up the service doorways. The building to the west of these was entirely his work, the site having been part of the stable yard in 1869, although he found earlier foundations and followed their line.

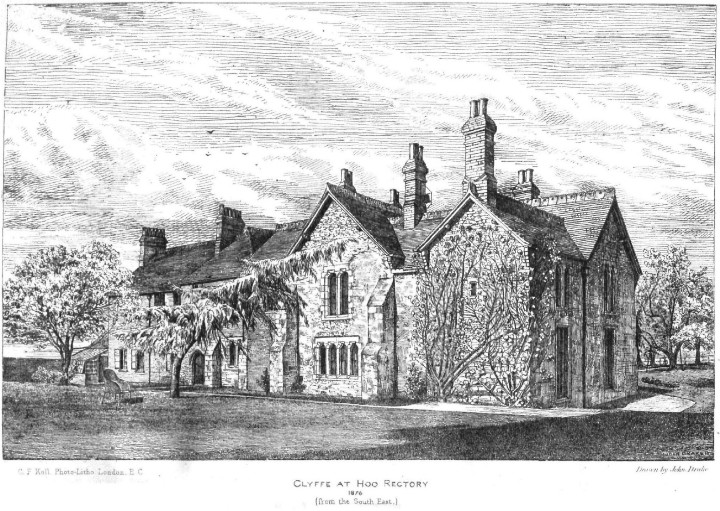

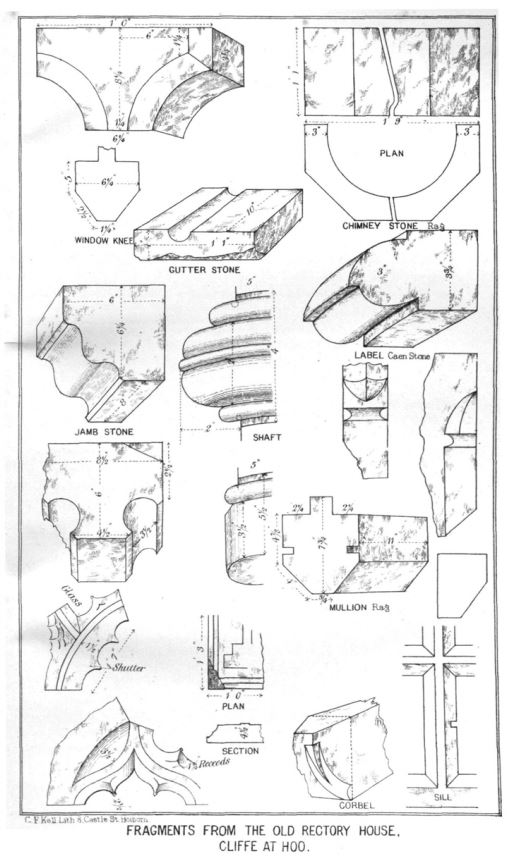

When, in 1870, the Rev. H.R. Lloyd commenced work on the Rectory House at Cliffe-at-Hoo. He left an account of what he did in Arch. Cant. (Lloyd 1883, 255) and illustrated it with an elevation and a plate of fragments of moulded stonework, but unfortunately gave no plan.

Prior to the selling of the Rectory into public hands, in 1972, permission was gained from the then incumbent rector, the Rev. J.J. Smith, for a survey of the Rectory and a preparation of a plan of the building.

We are thankful that, from the survey carried out, a plan of the ground floor can be shown in some detail although no attempt in the survey was made other than plot the outline of those parts known to be the Rev. Lloyd’s work.

In 1970 the doors were again to be blocked as the new section was to be separately occupied.

The great hall was once sub-divided by a floor and partitions into several rooms above and below, with remains of ancient windows built up in the walls. The stone walls remain of the hall to a height of some 9 ft., and in the rooms to the east, originally of two storeys, to 15 ft. All of the existing roofs are Victorian. The internal walls are plastered throughout and no ancient window-tracery remains. The Rev. Lloyd found a fragment of a shouldered (‘Caernarvon’) arched window and he used this design for all of his new windows, many of them larger than the originals.

The hall itself has three doorways in its west wall, a pair 3 ft. 6 in. wide, not quite centrally placed, and another 2 ft. 4 in. wide by the south wall. These Rev. Lloyd discovered by crowbarring out the three ancient buttery arches, from behind a mass of brick-chimney and fireplace masonry. From some broken stone steps, which were found close by, he believed that the smallest of these three arches led to a stone turret staircase, giving access to rooms over the ancient offices, which were to the west of the hall. All the doors are severely plain, with two-centred arches and broach stops at their bases, the two service doors having hollow gated. Here, a 1 m.-wide cutting, some 1.50 m. north of the late fourteenth-century screens passage, but the other remains in use. The north wall has a section of flint-and-stone banding outside, as in Cliffe Church, and also has a 3-in. plinth throughout its length and returning along the east wall. The south-western window retains their window seat that on the north-west matches it in size, but the other two appear to have been widened. The Rev. Lloyd found broken tracery (of ‘decorated’ form, with a rebate for a shutter) in the infilling of the south-east window. Both of the doors in the south-east comer of the hall are medieval. One leads to the parlour, the other to a brick porch in Flemish bond, known to Mr. Lloyd as the cellar. This door which has a mutilated label moulding, a flattened roll with a wide frontal fillet, could have led to stairs, as at Penshurst, or to a passage as at Meister Omers, Canterbury. A floor has been inserted in the hall which is divided by a timber partition and both are of Jacobean date. Two windows upstairs are of brick, probably contemporary with the 'cellar', which dates from c. 1680 and blocks the remains of a window of thin brick.

To the east of the hall are two rooms, both of two storeys, a parlour and an L-shaped room to the east. It is unlikely that these are contemporary, since the plinth on the north wall of the hall is continued around the parlour only. The east parlour wall has been thickened for a chimney and the Rev. Lloyd found a Tudor fireplace upstairs here although he suspected that the chimney-piece was modern: all the chimneys are all Victorian and an extension was made in front of the pre-1870 front door, which had been inserted in the north parlour wall. This extension contains the present hall and stairs. In 1870, the L-shaped room was open to the roof the Rev. Lloyd converted it into a study, with a bedroom above and put "replaces in the end of the south wing. In 1970, this was the kitchen, the Victorian fireplace being blocked by a solid-fuel cooker, and very few old features were visible. There are two small square-headed, blocked windows upstairs in the south and west walls. Although the room faces east, there is no sign of the piscina needed for a chapel. There has been reference to a chapel built in the house sometime between 1333 and 1348, but it is likely that it was elsewhere. Possibly the rector of Cliffe added a further private room beyond his solar, as at Croydon Palace, and the narrow extension to the south could represent a garderobe, similar in size to that at Old Soar. The plan may be much more complicated, awaiting excavation for its elucidation. The two large buttresses on the south parlour wall may show where an extension has existed, while the Rev. Lloyd found many fragments of stone work in the area to the north and believed a chapel to have been on this side. The present block could well have been a central range between two courtyards, as at Croydon. The fragments of stone were collected and built into a garden wall, which ran south from the west end of the new west block and which had largely collapsed by 1970.’

The Old Rectory at Cliffe at Hoo

BY THE LATE REV. HENRY ROBERT LLOYD, M.A

Reproduced by kind permission of the Kent Archaeological Society.

In 1870 I began to examine the old Rectory House, which was very much dilapidated, having been altered and patched about so as to obliterate nearly all its ancient features. During this examination it was found that the original Rectory House had consisted of, first, from the westward, kitchens (destroyed, but the foundations left in the ground, the site being the stableyard in 1870); then a great hall, latterly subdivided by a floor and partitions into several rooms above and below, with remains of ancient windows built up in the walls; east of the hall stood the withdrawing-room. The first set of windows were two-lighted and transomed, with tracery in the heads (as is apparent from what remains of the south-eastern window of the hall to be seen in the cellar, i.e. a brick projection on the south side and eastward of the hall); the tracery, however, was not found in situ, but built in loosely here and there to fill up old windows and other holes. This tracery shews rebates for shutters. These windows had stone side-seats in them, and their right-hand jambs had been destroyed to widen the apertures for modern wooden insertions. Rough jambs of chalk and rubble were then substituted for the ancient splayed jambs of hewn Kentish ragstone. These windows seem to have been violently taken down, and windows of the shouldered-arch pattern substituted, one or two heads remaining in their places, though much decayed. There was no fireplace to be found in any part of the walls of the old hall; probably it was warmed by an open hearth, as in Trinity College, Cambridge, and in Penshurst Place, Kent, the smoke passing away through louvre boards in the high pitched roof. The floor of the hall seemed to have been of small coarse glazed tiles. The western end of the hall Lad been perverted to a kitchen, and there we crowbarred out the three ancient buttery arches, from behind a mass of brick-chimney and fireplace masonry. From some broken stone newel-steps which were found close by, it is thought that the smallest of these three arches led to a stone turret staircase, giving access to rooms over the ancient offices, which were to the west of the hall. At the east end of the hall, on the south side, is a lofty stone arch with roll moulding, having a peculiar stop. The other arch, in the east wall of the hall, led to the withdrawing-room behind the high table on the dais. The fireplace in this wall is quite modern, having been cut into the old wall in 1870-71. The withdrawing-room probably is much as it ever was, except the window, which was so mutilated and altered at various times that its plan and exact design could not be made out, the old jamb-stones being dislocated and built in at random; it was therefore “restored " as a four-lighted, shouldered arch window. The door opposite to this window was the old front door in 1869. The doorway into the eastern room, now the study, contains the remains of one stone jamb of the ancient doorway; the arch stones with roll moulding having been found, displaced and fractured, under the study floor. The fireplace in the withdrawing-room is ancient, but the chimney-piece is modern, the design of it, as of the other chimney-pieces in the ground floor rooms, having been taken from an ancient fireplace of the thirteenth century in a house at Charney, Berks, figured in Domestic Architecture of the Middle Ages, by T. Hudson Turner: Oxford, Parker, 1851. The study fireplace is modern in place and design. The old fireplace (if there was one in this room) was in the west end. What the windows were cannot now be determined, unless they were like the one in the south side of it, which was a narrow loop, low in height, and with widely splayed jambs; probably this room and those above it were storerooms for the chambers on their respective floors. This room had been terribly abused; it had had a doorway cut into it on the north side, and had been used for a wood and tool house. As to the upper rooms, what was above the offices is not known; the hall doubtless had a high steep open timbered roof. The withdrawing-room has a room over it in which there had been an ancient window with deeply splayed jambs; the tipper part of it was broken off so that its ancient state could not be determined; a miserable wooden usurper we expelled from the ancient jambs to make way for the two-lighted stone window now there. The stone arch above was made of old voussoirs found in and about the house.

There seems to have been a communication between this chamber and one over the study adjoining it. This room and the little one at right angles to it had all their windows destroyed and filled in, and the floor having been removed they formed one lofty L –shaped room, used as the drawing-room in 1869, with the study below. The windows in these two upper rooms had stone jambs, and had been twice altered; they were so disfigured and imperfect that they were completed and restored as they now stand. The little window in the western wall of the smaller room, which was discovered built up in 1871, leads to the supposition that the room had been a storeroom. The fireplace in the larger of these two rooms is ancient; the back, composed of tiles laid flat, was covered with soot when it was found, on the wall being cut into for a new fireplace, the old one not being visible or known. There was a Tudor arched, thin bricked doorway in the north-east part of the back wall of this larger room, evidently leading into a first floor room at the north of it, long since destroyed. The foundation of the eastern wall of this destroyed building may be seen at the north-east angle of the house, where the old wall is abruptly patched up with a buttress, composed of fragments of the ancient work, quoin-stones, the lowest stone of a chamfered door-jamb with pyramidal stop, and one of the stones which formed the head of a two or more, lighted, shoulder-arched window. On the north side of the house, east of the front door, there are traces of building; also 011 the west side of it, farther off, in the base moulding there is the recess, with return of chamfered set-off, into which a wall, extending northwards, was built; and part of a fireplace was found beyond this wall, westward, with foundations of other walls. There was probably a small quadrangle here, and a larger one beyond it, for stabling and offices, entered by a large pointed arch, the remains of which were found about the place. The old stables (not older than the eighteenth century, if so old) were composed of hewn stones, arch pieces, jamb-stones, quoins, and other relics of the ancient house. There are the foundation remains of an old brick wall, parallel to the house, extending along the edge of the present carriage approach, towards the yew-tree; these were discovered in planting a shrub. The garden on the north side has evidently been a fish-pond, and here were found some ancient lead weights for a fishing-net. Some old keys, a silver penny of Edward I., a silver penny of Charles I., a silver coin of Elizabeth, a groat, and a copper token of Philip Sweet, a tradesman of " Strood, in Kent," dated 1652, were found about the ground. Quantities of hewn stone, quoins, door and window jambs, arches, four pieces of window tracery, octagonal chimneys, small pillars, jambs, nookshafts, two Purbeck fragments of tombstones with cross shaft upon them and illegible letters on the edges, and two pieces of benaturas, were found under the floors, and outside the house, in the ground, and in walls of outbuildings. It is said that a chapel had been attached to the Rectory House, which is probable from the remains of such work found here, and because the residences of such eminent^ ecclesiastics, as the rectors of the Peculiar of Clyffe, were generally furnished with a chapel for the daily celebration, as enjoined in pre-Reformation days. It was probably on the north side of the house, adjoining the study, with its window eastward. There were found some few pieces of a church window (having no rebate for shutters) among the fragments in and about the house, which possibly belonged to this chapel. There was no ancient timber found in the house, except two or three pieces of oak bearing marks of fire, as did many stones. The house had apparently been burned down at least once, and the state of some of the ancient stone work, with iron stanchions torn out of their sockets, transoms fractured, and mullions broken, suggested that it had suffered violence and perhaps pillage in 1378 from Wat Tyler's rebels, or in 1450 from Jack Cade.