Remains of the Medieval Sacristy of St. Helen's Church

By PJ Tester

Arch. Cant. Vol. XCVI

This church has been fully described in two articles in previous volumes of Arch. Cant. The earlier, by the Rev. I.G. Lloyd, appeared in vol. xi (1877), and the second, accompanied by a plan, by A.R. Martin, in vol. xli (1929). Both these writers drew attention to evidence of there having been a small building attached to the north side of the fourteenth-century chancel towards its east end, identified as a chapel or sacristy. The evidence consists of two small arched niches, one in the north (outer) face of the chancel, and the other in the east side of the second buttress from the end, these having been at one time internal features. Martin considered the former to have been a piscina and the other possibly a holy water stoup. Between the two buttresses the treatment of the chancel wall is dissimilar from the decorative coursed ragstone and flint facing of the rest of the fourteenth-century work, being of random rubble, and Martin considered this as indicative of its being a survival of an earlier chancel and that possibly the vanished building was pulled down when the chancel was rebuilt in the fourteenth century or soon after. Inside the chancel, a doorway — now blocked — has fourteenth-century mouldings and formerly communicated with the destroyed building. On the outside the rough rubble blocking of the opening is very apparent.

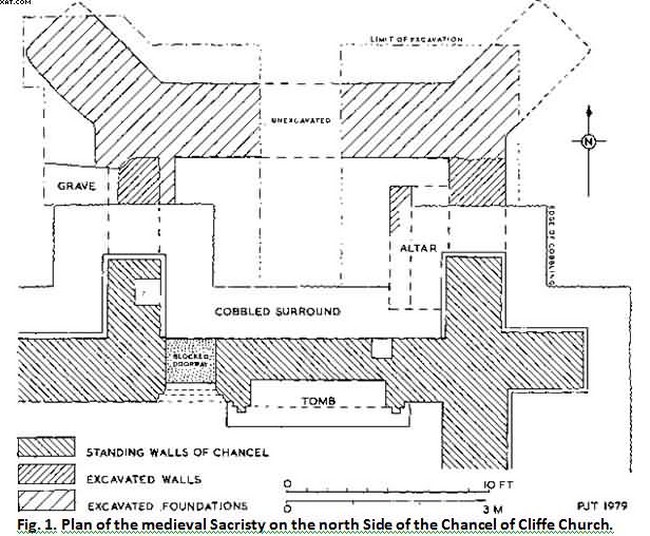

In 1978, the Rev. S.P. Gray, Rector of Cliffe, requested our Society to carry out excavations to ascertain the nature of the destroyed building, and in May 1979 a small group of our Members opened two wide trenches to reveal the features shown in the accompanying plan (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, the presence of a strip of concrete-set cobbling now runs at ground level round this part of the church, constructed recently to prevent surface water penetrate the base of the walls, and we were consequently not able to dig close to the chancel. Northward of this obstruction, however, we uncovered fragmentary remains of two ragstone walls and the wide chalk foundation of the north wall with two diagonal buttresses. It is thus possible to state that the building measured internally 14 ft. from east to west and slightly over 9 ft. in width, allowing for a slight setting back of the north wall on its foundations.

Parallel with the east end there was a wall, 1 ft. thick, plastered on its west face and neatly squared at the north end. The cobbled surface prevented a full examination of this feature which had apparently disintegrated at a point 2 ft. 6 in. from its northern extremity, but it almost certainly formed the front of an altar, the outline of which is restored conjecturally on the plan. If the wall was free-standing with a space between it and the end of the building, as seems probable, the mensa or top slab of the altar may have rested at the rear on a ledge or corbels.

Immediately adjoining is the small niche in the north face of the chancel, interpreted as a piscina. A careful search failed, however, to discover a drain-hole in its very eroded base, but in view of the disintegrated nature of the stonework this negative evidence cannot be stressed.

Reference has already been made to the blocked doorway form giving access from the chancel, and this is shown in a photo accompanying Martin’s article in 1929. As he noted, the blocking at the north end descends some distance below the internal cill, so it may be assumed that steps existed in the thickness of the wall. From our observations it is concluded that the floor of the sacristy was about 3 ft. lower than that of the chancel. When the sacristy was demolished and the opening blocked, an extension of the earlier string-course along this side of the chancel was inserted, this now being in a very eroded condition, whereas elsewhere the stonework of the string-course has been renewed in modern restoration. The fact that this insertion was not continued eastward of the blocking may be explained by the fact that to do so would have involved the labour of cutting into the wall, while the introduction of the feature during the construction of the blocking would be comparatively simple.

Both buttresses in line with the east and west walls of the sacristy have been extensively renewed in restoration, but the low-arched niche in the western of the pair is a surviving medieval feature, its floor being 1 ft. 3 in. square while the cill was about 2 ft. 6 in. above the old floor-level. Its purpose is problematical, for it has no rebate for a door or traces of hinges such as would occur if it had been an aumbry, and to Martin’s suggestion that it was a holy water stoup (though there is no trace of a basin and the floor is flat) I would add the conjecture that it may have contained a lamp to light the foot of the steep flight of steps leading up to the chancel.

Corbels in the chancel wall indicate the level of the sacristy roof, and from this it may be judged that the internal height of the building was approximately 10 ft.

To the west, the foot of a grave had been cut into the wall and footings, indicating that the uncoffined burial took place after the demolition of the sacristy.

Discussion. There can be little doubt that the destroyed building was intended primarily as a sacristy or vestry as its position in relation to the chancel is that commonly assumed by such structures in parish churches, as at Stone (Dartford), Crayford and elsewhere.

The occurrence of an altar would not be out of place in such a context before the Reformation. As for its age, I see no reason why it should not have been contemporary with the fourteenth-century chancel. Diagonal buttresses were rare before that period and the indisputable fourteenth-century Decorated moulded jamb of the entrance from the chancel is partly covered by the plinth of the later Perpendicular tomb. Martin’s observation that part of the chancel wall coinciding with the length of the sacristy is of rubble, contrast with the banded facing of the remainder, does not necessarily imply that it is of a different age. As this area would have been enclosed within the sacristy, it was not given the elaborate banded treatment employed on the exposed parts of the chancel, and was no doubt originally plastered — as were nearly all internal wall surfaces in medieval churches. There is no clue as to when the sacristy was demolished, but I consider it not unlikely to have taken place at the Reformation when the abolition of the medieval rites would have rendered obsolete the vestments and other liturgical ornaments, which the building was provided to accommodate.

[1] Martin stated that ‘a plinth has been inserted when the door was blocked up, to match that round the rest of the chancel’, but in fact the top chamfer of the actual plinth is well below the string-course and is not continued across the blocking.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Kent Archaeological Society.